Dizziness and Vertigo Explained: What Causes It and How to Fix It

In the broadest sense, our brain gets all sorts of sensory inputs from the body but if the inputs are 'wrong' or our brain can't make sense of them we can experience vertigo or feel dizzy. If you want to know more, read on…

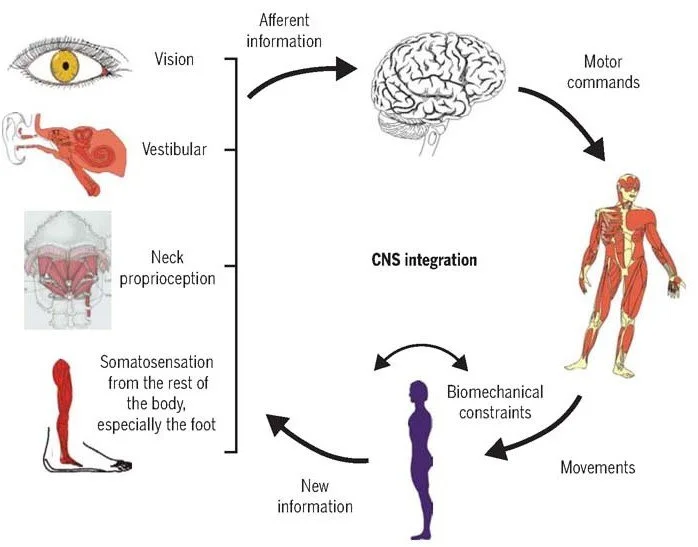

Our brain or central nervous system (CNS) broadly controls our body via two systems:

Motor systems that control the voluntary movements of the body.

Motor systems that control gaze, balance and posture (these can be viewed as stabilising systems).

Our ability to move and function properly depends on having a stable posture and good vision. The vestibular system, which develops first in humans, helps us orient ourselves relative to gravity and maintain balance. Information from the vestibular organs (in the ear) goes directly to the areas of the brain and spinal cord that control posture and spinal alignment. [1]

Your brain also gets inputs from eye movements which are coordinated with posture, locomotion, and movements of the spine and joints. The neck muscles, particularly the muscles just under the base of the skull (suboccipital), have an extremely high density of sensory nerves, essentially also serving as "balance organs." [2]

The "input" side of things all have to agree, or we experience the feeling of dizziness which is a non-specific term that describes a sensation of altered orientation in space. This includes feelings of faintness, wooziness, weakness, or unsteadiness. If it causes a false sense that you or your surroundings are spinning or moving it is referred to as vertigo. [3]

Dizziness can also be caused by many other things like standing up too quickly, hyperventilation, decreased cardiac output, anxiety, hypoglycemia, a change of glasses prescription, peripheral neuropathy, poor vision due to cataracts or glaucoma, hearing loss, motion sickness or drug side effects. [3]

The Postural Control System

“Input” “Output”

Figure 1: (Adapted from: Kristjansson, E., & Treleaven, J. (2009). Sensorimotor function and dizziness in neck pain: implications 1 for assessment and management. The Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy, 39(5), 364– 377.

The Role of the Vestibular System

The vestibular system plays a vital role in helping us stay oriented - a function that has remained critical since the earliest life forms. This sensory system essentially answers two fundamental questions for humans: [1]

Which way is up?

Where am I in relation to my surroundings?

The vestibular organs detect the forces of head movement and gravity, and convert this into biological signals. The brain then uses these signals to develop our sense of head position and surroundings. It also generates the reflexes needed to maintain our balance and equilibrium as we move around. [1]

The vestibular inputs are compared against information from other senses like vision and proprioception (body awareness) to keep us properly oriented during activities like walking or running. So this system provides critical orientation cues that allow us to navigate our environment seamlessly. Problems with the vestibular inputs cause vertigo.

Welcome to the inner ear…..

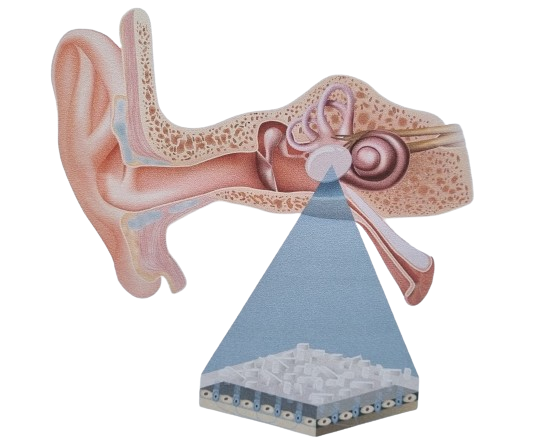

Figure 2: Utricle and Saccule

In your inner ear, there are two sensory organs called the utricle and saccule. These contain specialized hair cells that detect gravity and head movements. The hair cells have tiny hairs embedded in a membrane that has calcium carbonate crystals attached to it - making it denser than the surrounding fluid.

Because of these dense crystal deposits, the utricle and saccule are called the "otolithic organs." Their key role is to sense which way is up relative to Earth's gravity.

When your head tilts in different directions, the pull of gravity on these crystals shifts. Your brain detects this crystal displacement and automatically activates reflexes that make your muscles contract to adjust your head and body position accordingly.

So in essence, the utricle and saccule use these weighted crystals to continually monitor your head's orientation towards gravity and trigger postural muscles to maintain your uprightness and balance.

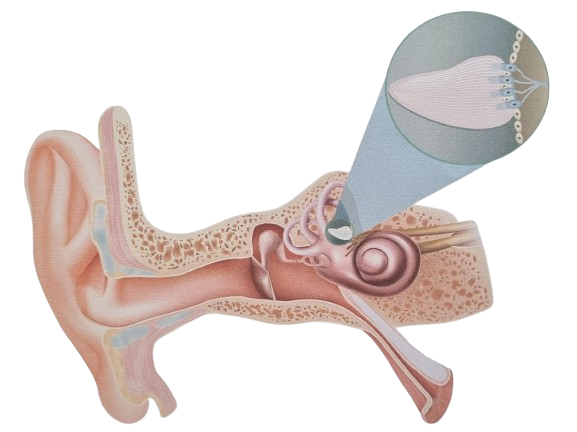

Figure 3: Semicircular canals and cupula

In addition to the utricle and saccule, there are three semicircular canals in your inner ear. These loop-shaped tubes are filled with fluid. Each one has a swollen area called the ampulla which contains a gel-like membrane called the cupula. Small hair cells are embedded in this cupula membrane.

The role of the semicircular canals is to detect angular head rotations and spinning movements. As your head turns, the fluid in the canals lags behind and pushes on the cupula. This bending of the cupula's hairs triggers nerve signals.

Your brain uses these signals to activate reflexes that contract muscles and help maintain your balance and equilibrium during motion. That's why the semicircular canals are called the "kinetic" reflexes, as opposed to the "static" gravitational pull sensed by the otolithic organs - they only sense the rotational accelerations that disrupt equilibrium during head turns and spins.

So what has the inner ear got to do with vertigo?

Vertigo, defined as an illusion of movement, always indicates a problem somewhere within the vestibular system. This system includes the vestibular organ, the 8th cranial nerve, the cervical spine, the brainstem and the thalamus and cortex of the brain. [3]

By far the most common cause is a problem with the vestibular organ itself. Your therapist, through taking a good history of your complaint and a thorough assessment, will need to rule out the other causes.

Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV)

BPPV is one of the most common causes of recurrent dizziness and vertigo. Around 1 in 40 people will experience it at some point in their lives. [4]

In BPPV, it's believed that some of the small calcium carbonate crystals that normally sit on the membrane of the utricle or saccule (the gravitational sensors in the inner ear) become dislodged and migrate into one of the semicircular canals. This can be a problem!

When these heavy little crystals get inside the semicircular canals, they get moved around by gravity when you change head positions. So, as you tilt or turn your head a certain way, these tiny crystal "rocks" shift and hit against the sensory membrane, causing it to fire off false signals about head rotation and spinning to the brain. This confuses your balance system, leading to the vertigo sensation.

In essence, the displaced crystals act like a plunger hitting the sensors, triggering overwhelming vertigo with certain head movements until the crystals get relocated properly.

The cause of calcium shedding is not well understood but obvious causes are trauma and viral infection. However in most cases there is no identifiable cause. As there is increased incidence of BPPV in the older population, age-related changes to the protein matrix have also been considered along with altered calcium metabolism due to hormonal changes in women. [4]

The classic symptoms of BPPV are:

Attacks are typically triggered by changing head positions - especially rolling over in bed or bending forward.

There's a short delay of a few seconds after making that head movement before the intense dizziness and spinning sensation starts.

The vertigo episodes don't last long, usually just 15-30 seconds.

During a BPPV vertigo attack, the eyes uncontrollably flick back and forth (called nystagmus) due to the confusing signals about head rotation.

With repeated movements that triggered the vertigo initially, the dizziness and nystagmus become less intense over time as the crystals get disturbed less.

In summary, BPPV causes brief but severe vertigo spells after certain head movements due to displaced crystals hitting the wrong sensors. The delays, eye movements, and fatigue patterns are typical characteristics of this inner ear disorder.

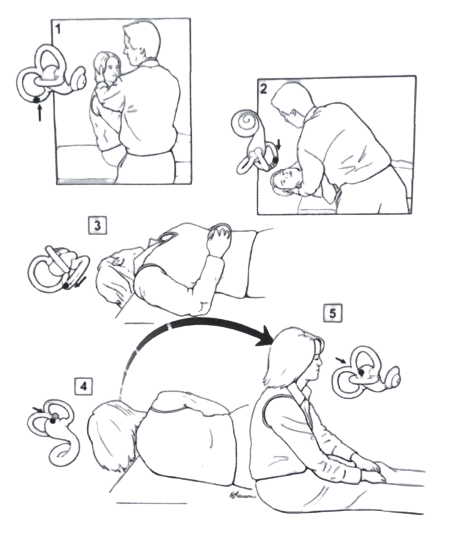

Here’s the good news!

There are manoeuvres that, when skilfully applied, can reposition the errant crystal and eliminate the vertigo immediately in over 80% of cases. These vary a bit depending on which semicircular canal is affected, but the most commonly applied technique is the Epley manoeuvre. [4,5]

Figure 4: The Epley Manoeuvre

Image © 2013 American Academy of Neurology. Fife TD et al. Neurology 2008;70:2067-2074

Your Neck and Vertigo: What's the Connection?

While most people associate vertigo (the false sensation of spinning) with an inner ear problem, emerging research shows that issues with the neck can actually be a major contributing factor as well.

The Neck's Role in Balance

To maintain balanced posture and equilibrium, your brain relies on integration of sensory information from your inner ears, eyes, muscles and joints - especially those in the upper neck area (see Figure 1). The upper cervical vertebrae especially have a very high concentration of specialized nerve endings called proprioceptors. Proprioceptors tell your brain where a particular bit of tissue is in space and its movement.

As described in this study, "The cervical spine serves as a 'core-pillar', providing postural information to the central nervous system and is considered a significant component of the postural control system."(6)

Problems Affecting Neck Proprioceptors

When neck joints become stiff or irritated, it can distort the proprioceptive signals being sent to the brain about your head's position and movements. This faulty information clashes with the signals from the inner ear and eyes, resulting in dizziness, vertigo, balance issues and nausea.

Common neck problems that can provoke this sensory mismatch include:

Whiplash injuries

Arthritis

Disc herniations

Postural issues/muscle tension

An imaging study shows even minor neck curves or joint misalignments can significantly alter the firing of proprioceptors.(7)

Dizziness originating from dysfunctional neck proprioceptors is often referred to as cervicogenic dizziness or cervical vertigo. Up to 1 in 5 dizziness patients may have a neck component contributing to their symptoms.(8)

If left untreated, the dizziness may become chronic as the brain struggles to integrate the conflicting signals. Treating any neck issues is crucial for alleviating cervicogenic dizziness.

Getting Help

Seeing a therapist trained in managing cervicogenic dizziness is recommended. They can identify any musculoskeletal causes through postural assessment, mobility testing and palpation of the upper cervical spine.

Manual therapy techniques and specific exercises can then be used to restore normal alignment and mobility of the upper cervical vertebrae. This resets the proprioceptive signals, reducing sensory conflict.

If you experience chronic dizziness, don't overlook a possible neck component. Getting your neck moving properly again may finally give you relief.

Luckily, at Clevedon Chiropractic, we can assess all these various potential causes for vertigo and dizziness, and treat appropriately giving you a great chance of complete recovery.

References:

Hain, T.C. & Helminski, J. (2014). Anatomy and Physiology of the Normal Vestibular System. In Vestibular Rehabilitation Contemporary Perspectives in Rehabilitation (pp. 2-18). FA Davis Company.

Vestibular Disorders Association - https://vestibular.org/understanding-vestibular-disorder

Bhattacharyya, N., et al. (2017). Clinical practice guideline: Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, 156(3_suppl), S1-S47.

Fife, T.D., et al. (2008). Practice parameter: Therapies for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (an evidence-based review). Neurology, 70(22), 2067-2074.

Image reference: Fife TD et al. Neurology 2008;70:2067-2074

Beinert K, Taube W. Cervical proprioception is diminished in patients with cervical spinal cord injury. Somatosens Mot Res. 2018;35(2):151-158.

Rohner SS, et al. Upper cervical spine subluxation alters proprioceptive input: a novel hypothesis with supporting data. Chiropr J Aust 2018;46:108–17.

Reid SA, et al. Cervical vertigo: an upside-down review. Clin Exp Pharmacol. 2022 Jun;49(6):446-459.